This article was originally published on Ferretbrain. I’ve backdated it to its original Ferretbrain publication date but it may have been edited and amended since its original appearance.

James Blish doesn’t get nearly enough love these days. Stroll into any bookshop and the most you are likely to find of his work is the SF Masterworks reprints of the somewhat inconsistent Cities In Flight and the renowned A Case of Conscience. It’s difficult to say for sure why only these two books are considered worthy of keeping in print, but a big clue lurks in many second-hand bookshops: from the late 1960s until his death in 1975, Blish had the honour of producing official novelisations of Star Trek scripts. There’s a certain kind of literary elitism which looks down on people who write adaptations of films and books, and while I’m not sure that’s always fair I think it is somewhat justified in Blish’s case: the beginning of his Trek books coincided with a sudden drop in the quality of his independent output – aside from the twinned novels Black Easter and The Day After Judgement, which together comprise the third part of the After Such Knowledge trilogy, from 1968 onwards none of Blish’s output is considered to be especially gripping or important by SF critics and fans. Perhaps Blish found that Star Trek novelisations were such a tempting prospect (heck, any official Trek tie-in is a licence to print money) he didn’t feel the need to try anymore, or perhaps the demands of cranking out 12 collections of Trek stories in 8 years was simply too draining.

The blame can’t be entirely pinned on Star Trek, however. Blish could be entirely capable of being mediocre on his own. Galactic Cluster, published in 1960, is a collection of early short stories by him, and while they aren’t exactly bad they’re not of the high standards that we know Blish could produce, and as such they are frustrating. Many of them seem to be on the verge of exploding into genius but never quite doing so – the sole unflawed gem is A Work of Art, a brilliant account of the apparent resurrection of Richard Strauss in 2161 and what happens when he tries to write music again. It is here that Blish manages to ask big, important, meaningful questions, as he does in his best work, while at the same time producing interesting and well-written hard SF. Blish can more-or-less handle characterisation, when he can be bothered, has a firm grasp of the scientific theories of his time and contradicts them interestingly and consistently, and displays more intelligence and thoughtfulness in his philosophical musings than anyone else writing in SF at the time. (To put things in context, J.G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick was still warming up at this point in time, and the likes of Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein were the big names in hard SF.) Blish, by rights, should have been huge.

But he wasn’t, because he wasn’t averse to cranking out mediocre stories to pay the bills. To Pay the Piper reads like a pitch for a Twilight Zone episode but falls flat. Beep relies on a plot twist which is far too obvious. Common Time and Nor Iron Bars are essentially both the same story: Nor Iron Bars covers precisely the same ground that Common Time did, less interestingly, and provides no new insights. The short novel Beanstalk, which concludes the collection, is interesting as a first sketch for The Seedling Stars and as a commentary on race relations but has dated poorly.

The main problem with Galactic Cluster is that Blish simply isn’t very daring or confident in the stories within. Cities In Flight was a bold future history of New York from the invention of antigravity to the end of the universe. A Case of Conscience dealt with Catholic theology to an extent which has been rarely matched within SF. By contrast, the stories in Galactic Cluster are just a little bit too tame. It is frustrating to watch James Blish acting entirely within his comfort zone, because I know when he ventures beyond it he can do so much better.

By contrast, James Herbert in his comfort zone is sheer fun, the horror novel equivalent of cheap ice cream: you know what you’re getting, you know you’re going to enjoy it, it doesn’t outlast its welcome and it doesn’t mess about. Herbert’s output is best described as “patchy”, and while I seem to recall being very impressed by some of his other books, I can’t remember much about them because I was 17 when I read them and it is possible I’d hate them if I went back to them. And all too often the results of him trying to extend his literary reach are more horrific than the topics he writes about. This must be why he does it so rarely.

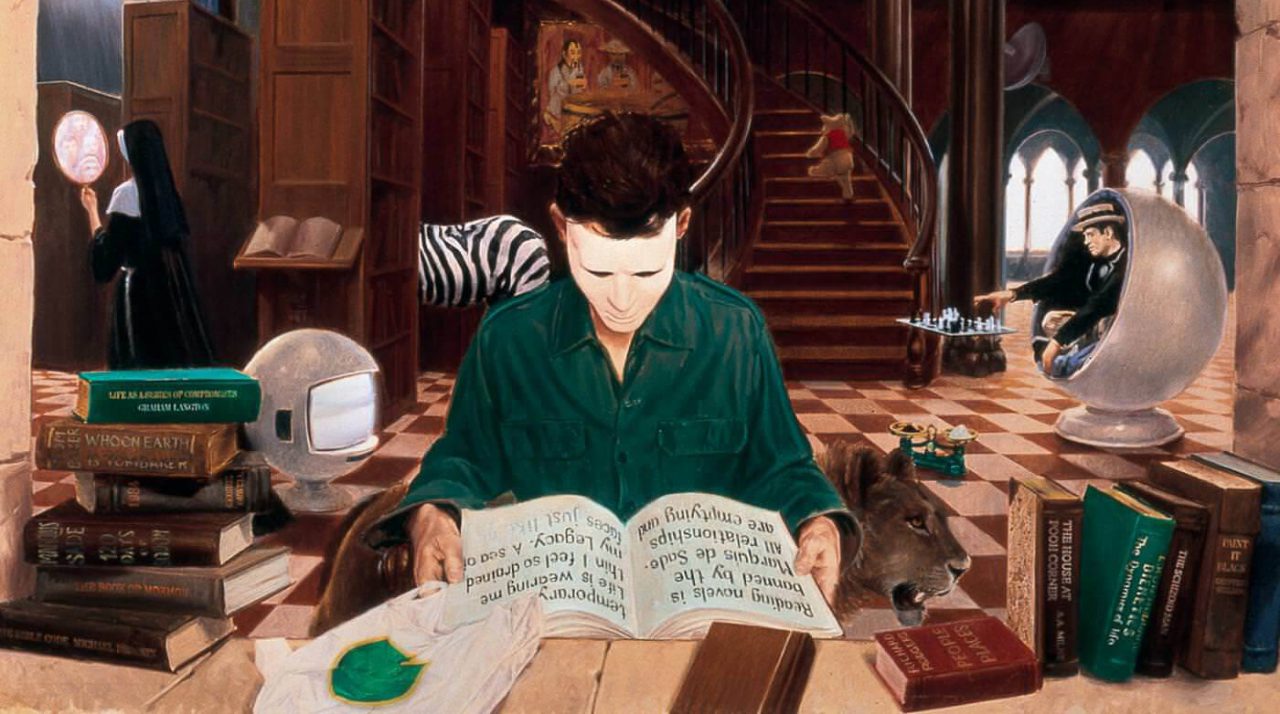

But I’m getting ahead of myself. James Herbert is a horror author who was first published in the 1970s, a couple of years before Stephen King. Those of you who remember Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace might be struck by the resemblance between real-life horror writer Herbert (who wrote a book about haunted locations called James Herbert’s Dark Places):

and fictional horror writer Garth Marenghi:

James Herbert is described by his publishers as “Britain’s number one horror writer” and “much imitated”, which is fair enough: Brian Lumley’s Necroscope books, for example, read like an unimaginative Lovecraft fanboy ripping off James Herbert’s prose style and writing formula. Oh wait…

Herbert used to work for an advertising agency, and in his early years relied on a simple formula to produce bestsellers. Use a workmanlike and unadventurous prose style. Assume that most of your audience read the Daily Mail, so don’t get too clever and occasionally make stabs at being politically incorrect. Throw in a totally hot sex scene, make sure all the violent or scary bits are unflinchingly and gruesomely described, and don’t outlast your welcome. To his credit, Herbert has moved beyond the formula and diversified his style – although he’s always sensationalistic – but at the same time he occasionally revisits his early writing style – and occasionally reinvents it.

Nobody True is an example. My copy comes to 502 pages, but the publishers printed it with large type, thick gaps between the lines and generous margins – sensibly printed, it would come to about 200 pages, comparable to Herbert’s original output. Herbert’s prose, as always, is workmanlike – it is more polished than in his first books, but it’s not more adventurous. The plot, however, displays Herbert’s intelligence and originality. James True, our narrator, is a murder victim who was killed while he was having an out-of-body experience. Left with nothing to do except eavesdrop on the police investigation and invisibly follow his loved ones around, frustrated by his inability to help them, True finds himself compelled to bring the serial killer suspected of murdering him to justice, as well as exposing the true villain. Unlike his early output, which always included steamy sex scenes between protagonist and love interest, or Random Victim #1 and Random Victim #2, the only sex scenes which take place are between the serial killer and corpses, and between three Arab men and a reanimated corpse. (The Arabs don’t know that the woman is a reanimated corpse, but they do beat her up, jerk off over her prone body, and piss all over her). Needless to say, those parts are incredibly – probably intentionally – difficult to read, and aren’t at all titillating.

The difficulty Herbert was faced with in writing a novel where nobody talks to the main character for 400 pages and the protagonist has little-to-no ability to affect the action must have been immense, and in the hands of a lesser writer could have been disastrous, but there’s a definite point to True’s experience. Every single lie, deception and fraud which formed the basis of his happy existence is laid bare for him as he investigates his own death, and he finds himself having to come to terms with that. This is not to say there aren’t problems with the execution: the book occasionally reads like a cheap and cheerful primer on astral projection from the Mind, Body and Spirit aisle in Border’s, and the somewhat unsatisfying New Age-spiritualist cosmology Herbert comes with is uninteresting (and thankfully doesn’t intrude too frequently).

Nobody True is fun to read once but not the sort of thing I’d ever want to read again. The same is true of Galactic Cluster. In both cases, their authors are writing well within their comfort zones, but somehow Herbert makes a virtue of it while in Blish it is a failing.

If you want my copies of either or both of these books, leave a comment by the end of the week.